2019.04.09column

アメリカでの日本映画の受容

3月1~3日アメリカのUCLAで開催された「The Art of the Benshi」のことを伝えるウォール・ストリート・ジャーナルの記事です。

Speaking for the Screen

A program of films introduced Los Angeles audiences to benshi, where live Japanese narrators explain silent movies’ action and dialogue.

By

David Mermelstein

March 5, 2019 5:49 p.m. ET

[‘Blood Spattered Takadanobaba’ (1928)]

‘Blood Spattered Takadanobaba’ (1928)PHOTO: NATIONAL FILM ARCHIVE OF JAPAN

Los Angeles

A vanished world reappeared briefly but intensely this weekend when the UCLA Film & Television Archive presented an immersive program titled “The Art of the Benshi” at the Hammer Museum’s Billy Wilder Theater here. The Japanese term benshi, let alone its application, is likely unfamiliar to most American moviegoers. But then the concept is largely foreign to present-day Japanese film fans, too. One imperfect but convenient description of the role is narrator, but that hardly does it justice.

Benshi emerged in Japan at the turn of the last century, in concert with the dawn of the film industry there. Early exhibitors everywhere struggled with how to make audiences understand the nascent entertainment that came to be known as motion pictures. And in their infancy, movies depended on some form of extra-cinematic narration. But by 1910 or so, as the grammar of film began to take shape in the U.S. and Europe, the need had faded. Not so in Japan, where benshi thrived well into the 1930s. Indeed, the most accomplished of them evolved into performers whose own popularity sometimes rivaled the films they were meant to elucidate. At least in part, this happened because narrative traditions in Japan differed from those in the West. Japanese drama always had a strong “informing” voice—similar to that of the Greek chorus.

With time, technological change, and the remaking of Japan in the years after World War II, benshi—whose art might be likened to that of old-time radio sports announcers offering vivid, even exaggerated, descriptions of play—became anachronisms. Yet the art form was never entirely lost; vintage recordings still exist, as does the master-apprentice relationship that accounts for its continuation. And as renewed interest in silent cinema took hold throughout the world—whether as nostalgia, cultural artifact or social history—the benshi tradition endured, even if it didn’t exactly thrive.

Michael Emmerich, a professor of Japanese literature, and Paul Malcolm, a film programmer, both at UCLA, with help from counterparts in Japan, decided to build on that slim recognition, first in April 2017 with a single program that elicited little notice but much enthusiasm and now with four ample programs over three days (March 1 through 3) that were consistently well-attended (and on Saturday night, sold-out) by Angelenos interested in silent cinema, Japanese culture and just plain novelty.

[Fannie Ward, Yutaka Abe and Sessue Hayakawa in ‘The Cheat’ (1915)]

Fannie Ward, Yutaka Abe and Sessue Hayakawa in ‘The Cheat’ (1915)PHOTO: NATIONAL FILM ARCHIVE OF JAPAN

The experience was a heady one, especially for those attending all four programs, each of which ran more than three hours. At first, it was frankly overwhelming. The silent films were often mere fragments of vast epics, so the narrative on screen was disjointed. And because the benshi performed almost entirely in Japanese, “soft” subtitles (that is, transparencies projected in real time over the images on screen) were necessary for the largely—but by no-means exclusively—English-speaking audience. In addition, live music, a feature of traditional benshi performances, enhanced the experience—with as many as five players (on violin, flute, piano, indigenous drums, and shamisen or guitar) grouped together under the leadership of Joichi Yuasa. Adding to the authenticity, many of the scores were original to the period thanks to the recent discovery of a trove of material long thought destroyed.

But the stars, naturally, were the benshi, who had traveled from Japan for the occasion: Ichiro Kataoka, dressed in a sober kimono, who had previously appeared in this theater in 2017; Raiko Sakamoto, wearing a frock coat that suggested a Japanese diplomat of the prewar era; and Kumiko Omori, whose small stature and brightly colored ensemble (avec beret) further helped set her apart from her male counterparts. Together, they reportedly represent roughly 30% of the world’s active benshi. Their declamatory styles, more than occasionally laced with humor or a topical reference, were different enough that by the end of the weekend, one might well have had a favorite. (It would be hard to beat the Betty Boop appeal of Ms. Omori, but Mr. Sakamoto’s outsize characterizations and vocal range also found favor.)

In a rare but historically accurate choice, the three appeared together, voicing different roles, in the films that concluded each of the two Sunday programs, 12 minutes of fragments from the family drama “Not Blood Relations” (1916) and 21 minutes of the fantasy “Jiraiya the Hero” (1921), complete with primitive special effects, specifically the metamorphosing of characters from human to animal form. More interesting still were the weekend’s three screenings, two back-to-back, of the extant seven minutes of “Blood Spattered Takadanobaba” (1928), a swordplay film with an intoxicated hero. (Yes, even in the silent era ronin drank to excess.)

The weekend also featured a welcome twist on “cultural appropriation,” with three American pictures given Japanese narration, the Laurel and Hardy short “Liberty” (1929) and two Cecil B. DeMille melodramas: “The Cheat” (1915), which earned Sessue Hayakawa, Hollywood’s first Asian star, the enmity of his fellow Japanese thanks to his playing a sadistic antiquarian who literally brands the film’s leading lady; and “Silence” (1926), thought lost until 2016, in which H.B. Warner faces the hangman’s noose for a crime he didn’t commit. Seeing pictures like these in such a context confounds our expectations—to say nothing of inverting popular notions attributed to Kipling about East and West never meeting.

—Mr. Mermelstein writes for the Journal on film and classical music.

グーグル翻訳の力を借りながらですが、日本の活動写真弁士について背景を詳しく説明し、そして、それを現在の3人のプロ、すなわち片岡一郎さん、坂本頼光さん、大森くみこさんが演じた様子をとても好意的に紹介して下さっているようです。

この3日間、UCLAロサンゼルス校でどのようなことが行われたのかは、早稲田大学にある国際日本学拠点のサイトをご覧ください。この記事を書いた記者さんは、日本映画のファンらしく、丁度一年前の今頃、ニューヨークで開催された「撮影監督宮川一夫特集」の記事も書いておられます。

とても大きな扱いの記事で嬉しいです。会場の一つジャパン・ソサエティーのスタッフお二人に3月の大阪アジアン映画祭でお会いした時の話では、満員盛況だったそうです。ニューヨークでの様子はロチェスター大学のジョアン・ベルナルディ教授から送ってもらった写真も使って、こちらで書きました。宮川先生の映像美を世界の人々が評価して下さっていることを、改めて誇らしく思います。

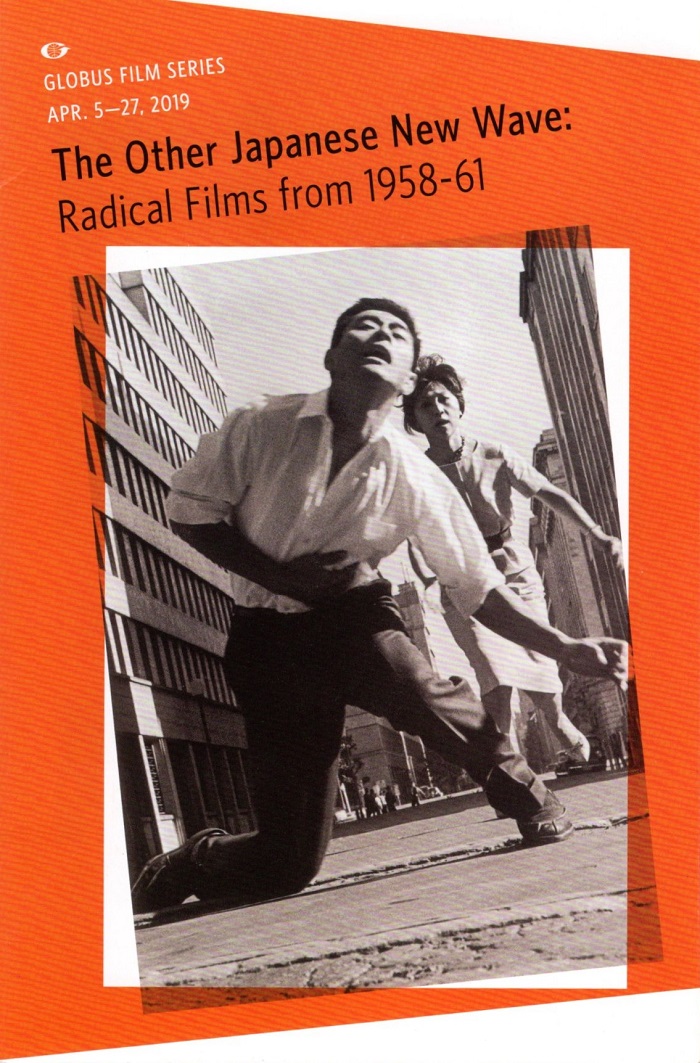

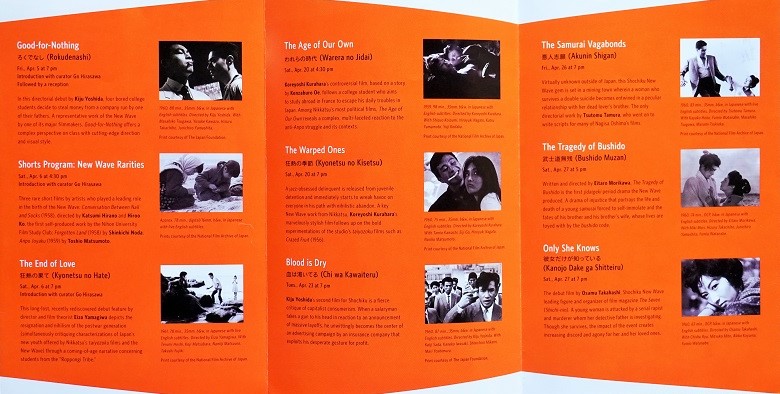

そして今は、5日から27日迄、ジャパン・ソサエティーで、「The Other Japanese New Wave:Radical Films from 1958-61」が企画上映中です。この記者さんがどのように書いて下さるのかも楽しみです。そして、その先に、依田義賢先生や宮川一夫先生、森田富士郎先生、中島貞夫先生らが後輩映画人を育て、連れ合いも多少なりとも関わった大阪芸大学映像学科の卒業生らの特集上映がされることを夢見ています。

4月7日(日)「ストップモーション・アニミズム展 in KYOTO」最終日のトークイベントに参加して下さったニューヨークにあるハミルトン大学准教授の大森恭子さん。3月から8月まで、立命館大学を拠点に活動写真弁士について研究されています。上掲UCLAでのイベントではビリー・ワイルダー・シアターで開催されたプログラムのうち、3月2日13時半~15時のディスカッションに登壇されて“The Soundscapes of Benshi”’のタイトルで発表されています。

大森恭子先生は、何年も前から澤登 翠さん、片岡さん、坂本さんとは知り合いで、坂本さんと片岡さんはハミルトン大学にも行っておられるのだそうです。とりわけ、片岡さんとは『雄呂血』に新しい音楽や弁士説明をつけるためにワークショップのようなものを主催し、成果披露のために2年前、UCLAで公演をされ、それが今年の催しにつながったとお聞きしました。

2月1日にAKPとKCJSの留学生さんたちが見学に来て下さいましたが、その時同行されたコルビー大学のキンバリー教授から「大学の同僚である阿部ヒデコさんが、弁士を調べている」とお聞きしたので、3月のUCLAでの催しのことをお知らせしようと片岡さんに連絡を取りました。「阿部先生とは10年前から知り合いだ」ということで、片岡さんから阿部先生に連絡して貰いました。いずれもアメリカの大学で研究されている日本人女性ですが、英語で発信されれば、活動写真弁士の存在が世界に広がります。

今年は、12月に周防正行監督の最新作『カツベン!』が公開されますので、この勢いで日本の無声映画の面白さ、表現の豊かさ、独特の弁士の語り芸が、世界に広まるよう願っています‼